My friend, where does the time go?

I ask myself that every day. Twice a day, actually. Once when I realize that it’s almost dinner time and I haven’t done the things I’d hoped to do. And then again at 11:30pm, when I realize that I haven’t even begun to go to bed. Between arbitrary changes in work priorities, a 176-mile round-trip commute (to an office where I mostly send emails and attend zoom meetings, because, you know: return to office), the schedules of three universities and two day-cares, and the random disruptions of stomach flu, snow days, and the occasional emergency room visit, each week feels like a crash landing through plan C (plans A and B don’t survive Monday breakfast).

Do you ever feel this way?

Most advice I see tells me that I should be able to fix this on my own. Like maybe if I learned some advanced kind of process management borrowed from car manufacturing, we could sort out the family schedule. Or maybe if I got a really nice planner, I could leap into a blissful state of clarity (my partner Caroline wrote a lovely piece about her ambiguous relationship with her own admittedly beautiful planner). Or maybe if I didn’t feel the need to re-watch all 16 seasons of Good Eats, I’d have more time to maximize my personal output. Maybe. But none of that wouldn’t get at the underlying issues of having too much to do, not enough support, and too few choices for how to live a good life.

The ways that we spend our time isn’t a personal (or family) issue. What options and what constraints we face are determined by our current moment in history and our locations in the larger social structure. Thinking about our schedules can tell us a lot about how apparently-distant and abstract forces (like the precarity of work, the isolation of many nuclear families, the poor state of public goods) effect our lives every single day.

I found some useful thinking tools in a book called Take Back the Economy: an ethical guide for transforming our communities, by J.K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy1 that can help us see how we spend our time and what larger constraints are at play. These tools can also help us imagine a better world.

We can’t life-hack our way to a humane schedule, but we can work together to create more options, more freedom, and finally stop crash landing through each week.

Here’s how.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

Follow along at home

Want to join me in an exercise in reflecting on time? Make a copy of this spreadsheet that offers these tools: a 24-hour clock and a well-being chart.

You can also find templates and instructions for these tools on the Community Economies website.

After you fill in the tools, we’ll circle back to think about what they tell you. If you can’t fill them out now, don’t worry. You can do them later. Or just keep reading for the take-home reflections down below.

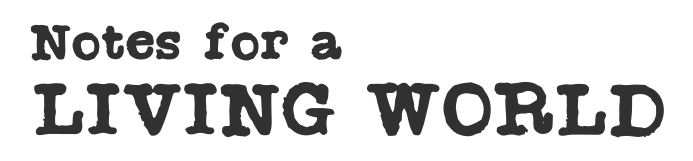

24-hour clock

The 24-hour clock is a pie chart that shows you where your time goes. Here’s how to use it:

On the spreadsheet, note down how much time of an average day you spend doing each of these kinds of activities: Paid work; Recreation; Care and up-keep; Rest and sleep; Travel.

For each category make a list of some of the things you do for each activity. For example, for “paid-work”, I might put: schedule meetings that no one (including me) wants, create a report that will sit in a folder forever unseen, look for different paid work.

The spreadsheet will chart your 24-hour clock.

Well-being Scorecard

This tool is just complicated way of asking: “how are you doing?” But instead of one answer, you’re going to think about 5 different kinds of well-being.2

Fill out the score card by looking at your clock and marking your well-being scores for the day described by your clock.

Here is more about each kind of well-being:

Material: This is having enough resources to meet your fundamental needs: food, shelter, more books, more shelves for the books, and so on.

Occupational: A sense of meaning and enjoyment doing the thing you do in the work you do all day. Note that this doesn’t have to include only paid work. Unpaid care work, volunteer work, and so on can also effect your sense of occupational well-being.

Social: This comes from direct personal relationships.

Community: Your feeling of connection to and support from your larger community surroundings.

Physical: This means having good health and a safe environment.

How do things look?

What do you notice when you look at your clock and scorecard? Do they send you any clear messages? Do you see any surprises?

For me, I notice an unexpected diversity of activities. Wage work takes up a huge amount of my mental space (and time in therapy), but when I look at it in the larger context, it doesn’t look like as big of a deal. Non-wage activities are a much bigger part of the picture. Care-work turns out to be an often comparable amount. At the same time, I also realize there’s more slack there to pick up. I should probably go and water some plants or enroll the kids in swim camp. I’ll be right back.

More surprising is that when I put together the little pieces of recreation and social activities, they add up to more than I expected. Right off the bat, doing this activity helps me recognize how all these little activities contribute to my well-being. Chatting with my neighbors only takes a few minutes, but it’s my main source of community well-being on most days. Writing this newsletter is so far from paid work, but it’s a big piece of my occupational well-being.

For Gibson-Graham, et al, this is an important lesson: The little things that you might not take seriously are actually important. They are cracks in the austere facade of life— spots where a more sociable, humane world peeks through. When I think about the benefit from the smallest amount of community engagement, I can start to imagine what a life would be like that was more deeply connected with folks around me.

What constraints and what choices do you have?

It might be tempting to look for ways to rearrange your schedule to increase your well-being. If you see a chance for an improvement, go for it. But if you’re like me, you’re probably doing the best you can, given your situation. Like I said at the beginning this isn’t about schedule-hacking your way to happiness.

It’s better to ask: what shapes the choices you have? And how could you have more or better choices?

This is where the large forces of the world show up in your personal schedule, which has everything to do with history, identity, and collective struggles.

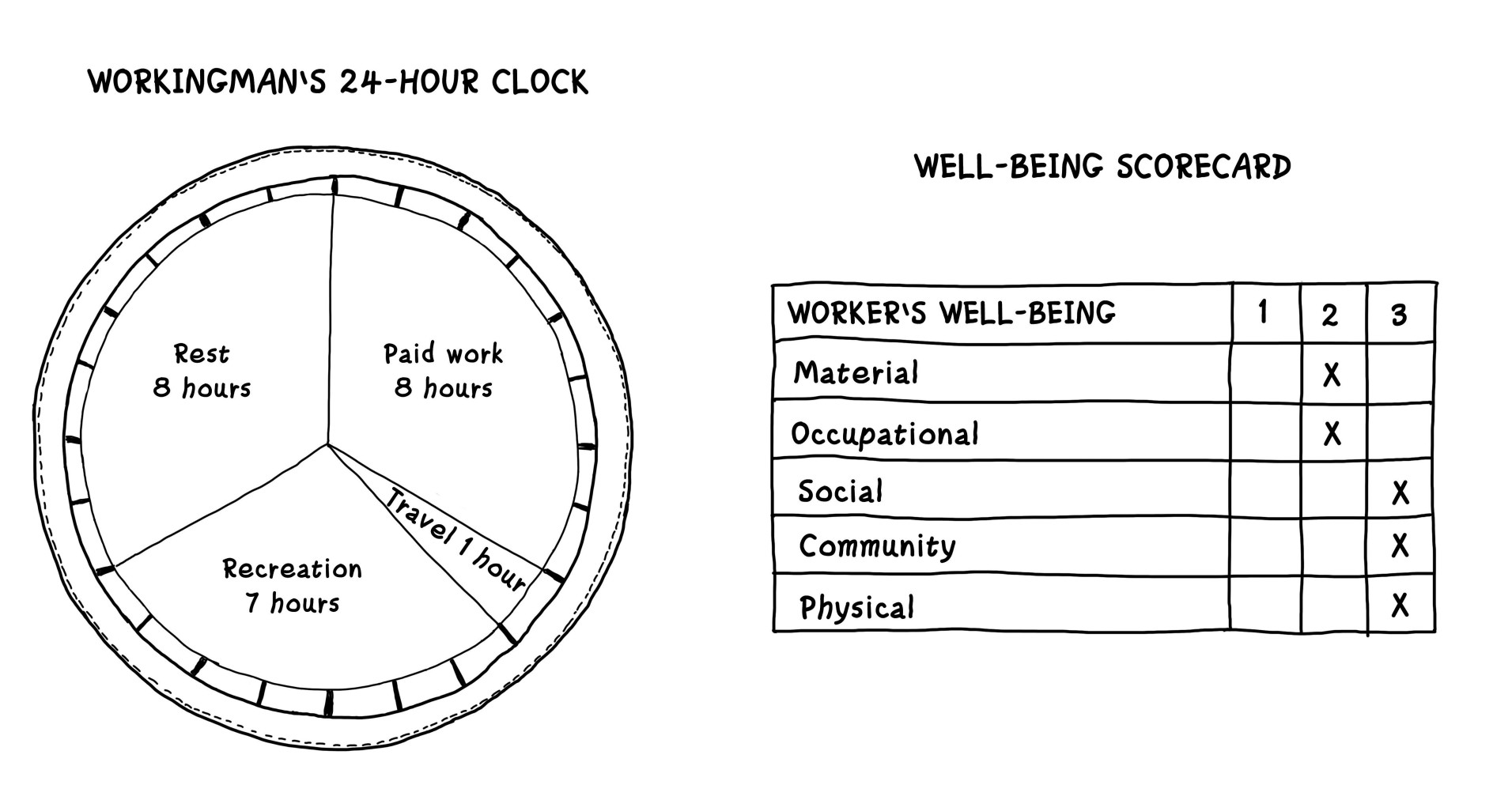

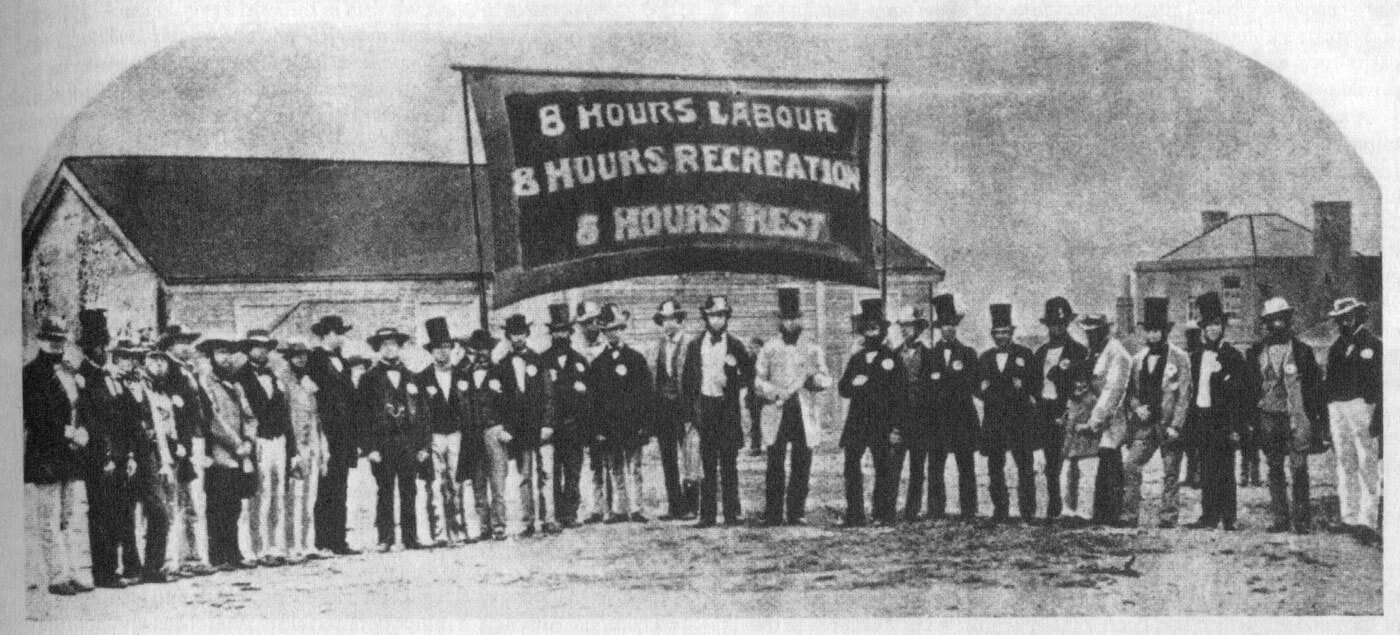

Gibson-Graham and collaborators give some examples that make this easier to understand. They imagine a 24-hour clock and well-being scorecard for a white male union worker in the 1950s. The clock is nicely balanced with 8 hours of rest, 8 hours of work, and 8 hours of recreation and it’s matched by pretty high well-being scores. There are many structures in the worker’s context that make this clock possible. Not least of all the collective action of unions. (“8 hours for work, 8 hours for rest, 8 hours for what we will” was a slogan from the first May Day parade in 1886 and was taken up by the early union movement). This worker’s clock looks very different from a factory worker’s clock 100 years earlier. Or from a contemporary sweatshop worker or gig worker. There is a lot of history compressed into a person’s 24-hour clock.

Each person’s clock and scorecard is also tied to other people’s clocks. In the example above, the male worker’s schedule is made possible by the unpaid care work done by his wife. Her clock features no paid work, but is full to the brim with all of the other tasks needed to run a household. You could further tie both clocks to farm workers and service workers in one direction and to foremen, managers, and owners in another. The whole world starts to look like a tangled web of choices and constraints.

How to change the clock

Thinking about how each person’s clock is linked to history and to other people’s clocks highlights the limits of trying to change things through individual choice. Sure, it would probably be better if people chose low-cost + high-connection activities (picnic at the park with friends) instead of high-cost + low-connection activities (speed boat racing? fancy watch collecting? swimming in money?) but that isn’t where most people’s time is going. Most people’s schedules have much more to do with:

the amount and kind of work they do to afford the basics

what services they can assume will always be available (healthcare, transportation?)

what options they have in their immediate surroundings

These aren’t things you can fix by yourself, no matter how good you are at scheduling or how nice your planner is. We are in the realm of collective actions. Gibson-Graham et al have some suggestions for how to make things better for everyone:

Better work, pay, and conditions. Paid work is a huge part of most people’s 24-hour clock, so it makes sense that the circumstances of work have a huge impact on people’s well-being. From being able to limit one’s working hours (while still earning enough to live well), to not being physically or emotionally damaged by the work one does, there’s a lot of room for improvement for people working in almost every field at almost every pay grade. Unions, direct worker-power, and labor law are three good tools for this.

Public Services. Publicly funded education, transportation, healthcare, recreation facilities, and so on also make a huge difference in the options people have. Such services create opportunities for people to connect with others, provide things to do, and reduce dependence on money.

Better social infrastructure. All forms of well-being are better undertaken with others, but, in the US at least, we live in a world that has been hollowed out of so many kinds of social connection. There are fewer organizations and clubs than there were in the mid-20th century. The car-centered large-store anchored shopping that dominates the landscape reduces to zero the chances of running into friends and neighbors while running errands. There is a whole world of “social infrastructure” that we simply don’t have. Shaping policies and projects back in that direction would make everyone’s lives richer.

There is no amount of life hacking that can make these changes. They have to be created by groups of people with the power to direct resources to them. And that requires working together. The good news is that the actions needed to create these opportunities also improve well-being.

An ethical and sustainable economy

The tools I’ve been sharing here are just one piece of a larger picture that Gibson-Graham and their collaborators share in Take Back the Economy. Each chapter presents additional tools that let the reader re-imagine every aspect of how we make and distribute things (i.e. the economy): from the ownership and operation of companies, to finance and banking, to property ownership. They ask us to think about how these realms impact our day-to-day lives and what we can do to make it better. It’s a great book, with much more to dig into down the road.

In the mean time, how’s your day going? If you could magically re-draw your 24-hour clock, what would it look like? Let me know in the comments. Let’s see if we can do something about it!

Learn More:

Take Back the Economy on the Community Economies website. This has links to all of the tools in the book.

Take Back Work Chapter on the Community Economies website. This has links and guides for the tools discussed in this post.

J. K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, Stephen Healy. Take back the economy : an ethical guide for transforming our communities. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, [2013]

I’d love to hear from you. What’s your vision for a living world? What projects and ideas are you excited about? What topics do you want to see here? What am I missing? You can reach me at Notes for a Living World, please send it along!

J.K. Gibson-Graham is a collective pen name for Julie Graham and Katherine Gibson.

Tom Rath and Jim Harter, Wellbeing: The Five Essential Elements (New York: Gallup Press, 2010