Did you read Lord of the Flies in school?

I have a strong sense memory of reading it in middle school— I was sitting on the sunny side of a hot school bus, with the sliding window stuck halfway open at an angle. I was badly motion sick and was trying to keep my cheek against the cool window frame while also shading my eyes from the glare. I kept reading because I wanted to get the assignment done so I could do something else once I got home. I felt like I was at the bottom of a milk carton that should have gone back into the fridge ages ago.

I hated Lord of the Flies. That bus ride was like a living metaphor for how the whole book made me feel.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

If you haven’t read it, I can’t give you a good summary because I don’t remember the details and I’m refusing to look it up. It involved kids (from a prep school?) stranded on an island with no adults. They try to govern themselves, but it goes badly. They form bands, go to war with each other, follow a dictatorial leader, live in terror of an imaginary monster, and fail to take care of themselves. I think there’s a pig’s head on a stake, covered in flies (the title character). Yuck. Get me off this bus.

I don’t remember the plot, but I do remember the lesson the book was teaching us— without the structures of authority and “civilization,” people (even children) descend into a horrible war of all against all. They can’t feed themselves or reach long term goals and for some reason they start painting their faces with blood. If there were subtleties, I missed them.

I didn’t like the lesson, but it did get lodged somewhere deep in my ideas about the world. I imagine that’s true for lots of other people (the book is apparently still read in schools), probably even for folks who didn’t read it. It’s a set of assumptions that has a deep history and shows up all over the place (Could Survivor, which is in its 43 season, count as a TV adaptation of Lord of the Flies?).

The thing is that it’s a fantasy with little relation to what people actually do when they find themselves suddenly cutoff from their familiar systems.

Rebecca Solnit has a book about disasters called A Paradise Built in Hell that is a perfect (nonfiction) counter to the worldview of Lord of the Flies. It’s a book well worth reading. I’d like to share a few ideas from it that stand out to me.

Paradise Built in Hell is about what people do during disasters (like earthquakes, floods, heatwaves, and one accidental ignition of 3,000 tons of explosive powder). What actually happens when all the systems, routines, and norms are disrupted? On the way to answering, Solnit tells amazing stories of a number of specific disasters and folds in great introductions to many egalitarian strands of political thought and history.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Ian, I’ve been thinking about this book. As chance would have it, I wrote most of this post before the storm hit, but it seems all too relevant now. Maybe there is comfort here, since Solnit’s book is all about the amazing resilience that communities can show in the worst circumstances.

Kitchens for a calamity

From the 1906 San Fransisco earthquake, to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and from the London blitz during WWII to the evacuation and clean-up after the 9/11 attacks in New York, Solnit finds similar stories in all cases.

There’s an complex ambiguity in the way Solnit describes the disasters. On the one hand, they are obviously terrible. People are hurt and killed. They loose their houses and are displaced. People go through impossible situations and experience deprivations. And, like everything in modern society, the people without economic and political power suffer the worst.

The destruction is the part familiar. It’s what newspapers report and it’s the images that show up on the social media feed. Watching Hurricane Ian from afar, this is definitely the part I see. As far back as you go, images of buildings destroyed and people looking despondent have gone along with reports of disasters.

But Solnit reveals another aspect that is harder to see, especially from the outside— the way that people act and organize in the face of bad situation. The initial moment of destruction and fear passes surprisingly quickly. And then most people get it together, stay calm, and start helping others, often with good humor. Time and again, Solnit found people describing their disaster experience as a time of joy and connection.

Not only do they help each other out of immediate danger, people start organizing themselves and solving problems. Even with destruction all around, soon folks cobble together a new world for themselves in which:

Many of the old hierarchies, social divisions, rigid roles are abandoned.

People share what they have and help out without any kind of payment, accounting, or market.

People organize creative and effective ways to meet their immediate needs.

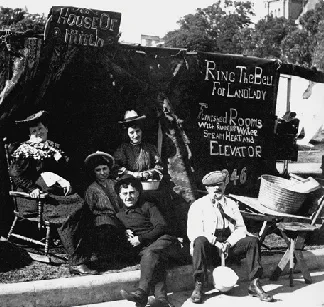

For example, after the 1906 San Fransisco earthquake a beautician named Amelia Holshouser climbed out of her wrecked apartment, made her way to a park, and stitched together blankets to make a shelter for 22 people and started a soup kitchen with a single tin can and pie plate (everyone had to take turns). Others brought her supplies, equipment, and even a few more plates. Pretty soon she was feeding 200-300 people a day. A group of miners from Nevada set up a wagon delivery service to get her food to people who couldn’t make it to the kitchen. Hers was one of dozens of impromptu soup kitchens setup, many with hilarious names and signs: One was called “the appetite killery,” another offered “rainwater fritters with umbrella sauce,” another had a sign that said, “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may have to go to Oakland.”

Grocers pulled food out of their wrecked stores and set it up on the street to give away. Butchers hired extra help to more effectively hand out meat to people in need. Meanwhile, rich tourists were horrified to find that they couldn’t buy their way to the front of the line.

The ways people organized themselves in many of these disasters sound like descriptions of pie-in-the-sky utopias, except they aren’t. They are just what regular people do when tossed out of their usual form of life into a hard situation.

It’s exactly the opposite of what you might expect from watching disaster or post-apocalyptic movies, listening to government officials, seeing the news, or, indeed, reading Lord of the Flies. In most real cases, there isn’t chaos and panic. People don’t create bands and start fighting and stealing from each other. There aren’t temporary warlords hording provisions. And no one puts a pig’s head on a stake.

Actually, it’s wrong to say that no one acts like that. In most of the cases Solnit looks at, the people who had been in charge, and people who really want the old hierarchies to continue, immediately start acting like characters from Mad Max. They bring in men with guns, who start shooting innocent people and hording supplies. They disrupt and shutdown people’s self-organization and reimpose markets, bureaucracies, social stratification, and traditional roles. In the process, they end up creating a whole new disaster, often one worse than the original one. Solnit calls this “elite panic.”

So, in San Fransisco in 1906, the mayor brought in the national guard and gave them orders to shoot-to-kill anyone thought to be out of order, which included: walking alone, walking with other people, being a woman walking in the road , being a man walking on the sidewalk (unless it was the other way around), or not following an order, no matter how obviously wrongheaded. Then they started dynamiting buildings in an effort to contain a few dwindling fires and ended up starting much bigger fires that destroyed the city. Thanks, guys.

Just to be clear, I’m not on Team Disaster. They are terrible and the folks effected need all the support they can get (though it turns out to be far better to give folks resources and leave them to it). But these extreme events do reveal possibilities that are hidden during every day life.

Lessons to learn

From all the stories, Solnit draws out a few larger points that are worth noting:

Self-organization, altruism, creativity, and care are a kind of default setting for people that gets activated in the right situations.

This suggests that a humanely organized world could be possible, even when nothing is on fire.

Regular people can get along great without central control, especially if they are given the resources they need.

The violence involved in re-establishing the systems highlights the foundation of violence (or threat of violence) that keeps the systems in place the rest of the time.

The social organization of a place can be reconfigured in a moment. Never mind a slow arc toward freedom, an egalitarian world of mutual aid could be in place before dinner.

Even though the disaster utopias Solnit describes last for only a brief time, those that live through them often carry a new consciousness of what is possible.

What if I had read this book as a kid instead of Lord of the Flies? I’d need a time machine to send a copy back to before it was published, and learning about things that would happen decades in the future would probably cause problems. And while I was at it, I’d also want to send along some stomach soothing ginger pills to help with the bus ride.

But setting that aside, what would it mean if instead of carrying around this baseline image of kids descending into viciousness, I had the image of people building themselves soup kitchens and thinking up funny signs?

What a different image of the world. We’re taught that a thin veneer of civilization hides savagery, but these stories show that it’s more like there’s a fragile shell of meanness hiding oceanic reserves of solidarity and creativity. It think an image like that would have felt a lot better.

Rebecca Solnit, A paradise built in hell : the extraordinary communities that arise in disasters. Viking, New York, 2009.

I’d love to hear from you. What’s your vision for a living world? What projects and ideas are you excited about? What topics do you want to see here? What am I missing? Let me know in the comments.