Did you play pirates as a kid? I did. I grew up far from the ocean, but we had an old timber-framed barn that stood in for a sailing ship perfectly. Climbing the wood-pegged ladders to the upper reaches of the barn felt like scaling the rigging to a topsail’s yardarm. I still feel a little bit like a pirate whenever I’m on a ladder taller than my head.

When my kids started playing pirate, I felt a little strange about them pretending to be ocean criminals. Is it ok for them to play villains? It’s probably is fine. But also: as I dug into the actual history of pirates, they look a lot less like villains than I thought.

I’ve found that pirate history has more lessons for creating new worlds than I expected.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

I got to thinking about pirates for the standard reasons:

I loved every minute of Our Flag Means Death.

By the end of the summer my cut-off shorts had frayed to a pirate-like extent.

My kids (ages 3 and 5) maintain a full library of treasure maps and armory of stick swords, and they yell “arg matey!” whenever standing on top of something more than 18 inches off the ground.

There was also a brief mention of pirates in the David Graeber essay on liminal democracy that I wrote about a few weeks ago.1 I’ve been following the footnote trail from that piece and found some great stuff about the underground/working-class world of 1700s Atlantic port towns, which wasn’t much like the picture I have from Colonial Williamsburg and the Ox Cart Man. Instead of folks quietly trading goose feathers for wintergreen candies and using sticks to roll around hoops, that ocean-facing world was wild, raucous, and constantly on the verge of becoming totally ungovernable. Pirates fit right in.

This strand led me to my beach read for this year: a book on pirates by Marcus Rediker called Villains of All Nations.

Here’s a few things I learned about pirates. This only applies to the so called Golden Age of pirates, 1716-1726. Piracy was different before and after this fleeting moment.

Pirates were real.

I’ve always thought of skull-and-crossbones pirates as having about as much to do with real ocean-going criminals as dragons have to do with dinosaurs— basically folklore inventions, only vaguely related to reality.

But for a brief time pirates were a significant, unified, self-conscious presence on the oceans. About 4000 people turned pirate over the course of ten years (1716-1726) and captured about 2,400 ships. They flew black jolly-roger flags, really liked rum, and at least one had an eye patch and peg leg. These are all true facts.

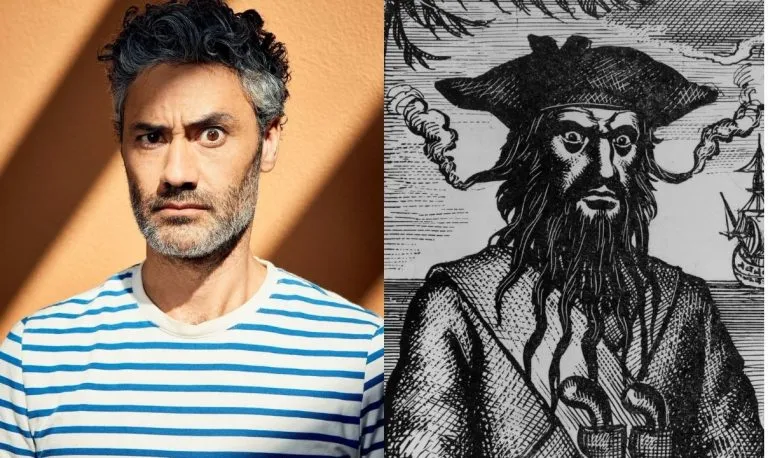

Also, if you watched Our Flag Means Death, know that: Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet were real people. Blackbeard was one of the most feared pirates of the time and often appeared wreathed in smoke saying that the devil sent him. Bonnet was a hapless rich guy who left his family to become a gentleman pirate. Oh, and they actually sailed together.

Here’s an episode of the Imaginary Worlds podcast about the historical basis for Our Flag Means Death.

There was literally a pirate code

Pirate ships usually had written constitutions, called articles, that outlined the rules and procedures for the ship. The articles were very consistent from ship to ship and many pirates seem to have been meticulous in following the procedures. New pirates signed the articles and swore an oath, promising to not attack, steal from, or cheat other pirates. Although totally outside all state authority, pirate ships weren’t a free-for-all— they were consciously constructed mini-societies.

Pirate ships were democratic.

While navy and merchant ships were under the absolute authority of the captain (who’s powers included whipping and executing sailors), pirates were very careful not to give anyone too much authority. They did not create mafia-like chains of command or tolerate dictatorial captains. Insulting the crew or threatening to make them walk the plank was a quick way to be made “governor of an island,” a euphemism for being stranded on a scrap of sand and rock in the middle of the ocean. Many became pirates to escape the brutal authority of captains and didn’t want to recreate the same conditions.

The ships operated as floating democracies. Pirate captains were elected and could be removed at any time. Even then, captains only had power during a fight. Otherwise, the day-to-day operation of the ship was run by a quartermaster, who was also elected from the crew. All the larger decisions, such as where to sail, when to fight, and what to do with captured ships, were decided by a council made up of the entire crew.

Pirates escaped exploitation and created a new world for themselves.

Nearly all the pirates came from the ranks of common sailors, who were recruited (sometimes by force) from the poorest people of the harbor towns and surrounding countryside. Sailors in general, and especially those who turned pirate, had a clear class-based read of the situation (which many explained at length during their trials and executions) that wouldn’t have been out of place at a union rally 200 years later. It was obvious to them that global trade completely depended on their labor and that the ship owners were making a fortune while they got a bad deal.

And it was a tremendously bad deal, sailors often got barely enough to eat (and that hardly edible), worked incredibly hard, and were exposed to extreme danger (one 240 person ship managed to rack-up 280 deaths during a single voyage). The pay was terrible and they regularly had their wages stolen by the captains and owners. Pirates often talked about their “being badly used” as the reason they became “freebooters” (a great synonym for “pirate”).

And so, within their outlaw realm, they created a world that was defiantly egalitarian. They did away with the rigid hierarchy of merchant and navy ships— for example, anyone could dine with the captain whenever they wanted. They literally tore down the walls of the private officer cabins so that everyone would share the same space.

Without external people taking the profits, they could grant themselves plenty of provisions and leisure time. Beyond that, pirates divided captured loot based on shares, with only a small difference between the largest and smallest share. The arrangement made them essentially co-owners of the venture. Pirate ship as worker co-op— who’d have guessed?

Even more: they set aside a portion of each haul as a mutual fund that paid out compensation for injuries (funding peg legs, eye patches, and hook hands, I assume) and even enabled some to retire to pirate island communities. This was a world totally different from the rigid hierarchies and grim exploitation of just about anywhere touched by European power.

Pirates were legitimately wild.

For all the charters, councils, and retirement funds, pirates were also legitimately wild. They literally used swords to open bottles. One crew destroyed 2/3 of their provisions during a three day Christmas celebration. They stole wigs from merchant captains, staged mock trials of each other, and raised blasphemous cursing to an art form.

They lived like people who, locked in a race with death, know they are going to lose. Indeed, if a pirate avoided capture and execution for two years, they were already an old hand. The people who chose this life were clear that they preferred to die pirates, rather than live as laborers (not that sailors could expect to live much longer). Some pirates swore oaths to kill each other before being captured. One kept a power keg nearby so he could blow himself up on short notice. There was once a crew that sang and cheered as fire raced toward their ship’s 2,000 lbs supply of gunpowder (only the younger pirates tried to put it out). One captain summed up his motto: “A merry life and a short one.”

And with all of this, they went ahead and put pictures of skulls on their flags. Which, if you think about it, is pretty intense branding. Terrifying to the ships they chased, but also a grim joke to themselves. Like I said, they were way out there.

Pirates freaked out the authorities.

Governors, mayors, preachers, and merchants were all beside themselves about piracy. The attorney general of South Carolina opened Stede Bonnet’s trial saying that piracy was “so odious and horrid … that those who have treated on that Subject have been at a loss for words.” The great New England killjoy, Cotton Mather, demonstrated this when giving a speech at an execution: “Oh! the Folly. Oh! the Madness of wicked men!” I can picture the dour puritan turning red and accidentally spitting a little as his wig slipped a bit at the thought of such disorder.

The extremity of the official war against pirates highlights how upset the authorities were. They brought the full strength of the British navy against the pirates. They offered to pay for the severed heads of especially hated freebooters. There were mass executions of not just pirates, but also of people who helped or traded with them, and even sailors who refused to fight them. Bodies were chained up on walls and heads were displayed on pikes. It was purposefully gruesome. All for what was primarily a crime against property. Oh, the madness of wicked men.

Piracy was so upsetting partly because it made a dent in the tremendous profits of the time. The merchants were not getting the return on investment that they wanted. But officials were even more worried about the example that the pirates set. They were explicit— they worried that sailors would refuse to submit to the miserable conditions at sea and that even townspeople would start to get ideas about equality. Given how tenuous the social control of the time was, maybe they were right to be nervous.

Most frightening for the authorities was the very real possibility that the pirates would become strong enough to set up permanent settlements beyond the reach of the colonial powers. There were parts of the Bahamas, Bermuda, Jamaica and other islands where the population was starting to side with pirates against the authorities. There’s a thread here that would be worth following of the places that were always about to slip out of central/colonial control. More to learn.

Although the pirates were generally too focused on their own thing to have much interest leading a revolution, just their example of a different way of life, operating by different rules, had a potential to inspire others by opening up new imagined possibilities. Maybe kids playing pirate is a distant echo of that imaginative space.

Just to be clear, I wouldn’t want to be a pirate. There was a foundation of violence and desperation that isn’t for me. Also, I get seasick sitting on a porch swing.

And I’ve been focusing on just a part of pirate life. There are other parts, like the lack of gender balance, hazing of new recruits, torture of captains found guilty of mistreating sailors, drunken accidents, and inconsistent stance toward the slave trade that were less laudable.

Still, I think there are lessons here. At a minimum, these “golden age” pirates were an example of people who recognized their collective power to change the rules by which they lived. They also showed that the brutal discipline used on navy and merchant ships wasn’t technically necessary— an egalitarian, democratic, festive approach to ship management also worked.

The bigger point for me, though, is the simple fact that they created functional democratic societies in a crazy situation. The wild roughness of the pirate world shows that democracy isn’t a hothouse flower in need of elaborate decorum, classical educations, and Doric columns.

So a question to think about: what are the minimum requirements for a functioning democracy? What do you think?

Maybe the pirates can point to an answer.

Here’s a hypothesis: Participatory democracy can spring up anywhere people treat each other as equals and recognize that they have a common lot. Pirates were aggressively willing to defend both ideas.

Surely, if a bunch of death-crazed, foul-mouthed sea robbers could manage it, anyone else could if they wanted to. Right?

Moments before posting this I found out that there’s a posthumous David Greaber book called Pirate Enlightenment coming out this winter. I have my winter holiday reading picked out!