I thought I’d stop feeling nervous once the US midterm elections were over, but I didn’t. And now I’m already grossed out by the 2024 elections. I realize that the feeling isn’t about the score card of who wins a particular election cycle, though that makes a huge difference. It’s more a feeling of dread about the whole game of US politics. Is it all falling apart? Or more accurately, are the people who are taking it apart going to succeed?

Watching US electoral politics feels like watching people play Jenga with dynamite in front of a dam. Except some of the players are wearing hockey gloves and some are rooting for an explosion. I care about the outcome, but I’d rather them do something different.

So, finding present so dreadful, I’ve been thinking about history. Does a longer view help make sense of the current crisis of democracy? You can probably guess my answer. The history isn’t comforting, but might help turn dread into resolve.

I found a podcast that does a really good job of telling the history of democracy in the US. It’s the 2020 season of a show called Scene on the Radio, from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. The series is called “The land that never has been yet.” It’s hosted by John Biewen and Chenjerai Kumanyika, who are very good at making radio. I listened to all 12 episodes straight through, twice. Then I read the transcripts. And I have them queued up for another listen. It’s that good.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

These episodes look at US history from the Revolutionary War to the present, paying attention to questions that often aren’t part of the mainstream/school-text-book version of history. They ask how democratic was the US meant to be? When has it been in crisis? What roles have money and authoritarianism played? And how have people fought for a more inclusive and representative country?

The story they tell is far from the benevolent enlightened progression that I learned as a kid and still hear. Instead the story is about conflict and struggle, elite violence and popular resistance, and an ongoing fight to finally create a country that lives up its basic promises.

Here are a few thing I learned from the show:

In the US, there has always been a conflict between democracy and authoritarianism.

The current right-wing fight against democracy (through voter suppression, gerrymandering, court stacking, lying about elections, and so much more) is part of a long legacy. From the beginning of the country there have been people who want to use the government to maintain hierarchies of wealth, race, gender, and so on. This faction has seen democracy (giving regular people a say) as a threat to that project. They have consistently used laws, courts, police and military force, and mob and vigilante violence to keep the structures in place. I know they didn’t all look like the Monopoly guy, but that’s how I’m imagining them.

The conflict between hierarchy and democracy is a theme through the Scene on the Radio series. There are many moments in US history that look very different with this perspective.

One of the biggest might be the writing of the constitution. E2: “The Excess of Democracy” tells the story:

After spending the Revolutionary War hearing about freedom and fairness, regular people took the promise seriously. Right after the war, working people in the new states started pushing for economic reforms. Most dramatically, farmers in Massachusetts blockaded courtrooms to stop foreclosures and debt trials (historians call this Shays’ Rebellion). Boston merchants had to hire their own private mercenaries to shoot cannons at the protestors so that judges could get back to seizing farms and giving them to creditors. It must have been inconvenient for the merchants, but I have trouble feeling bad for them.

Rich people and slave owners (including those familiar names: George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton) saw that if things kept up this way they weren’t going to be able to go on being rich and keeping humans enslaved.

And so, in the summer 1787, 55 white men, mostly wealthy and almost half slave owners, went to Philly and locked themselves in hot room with their itchy wigs, closed the windows, and designed a new government. Many of them were explicit about their goal to reign in popular rule. They were also explicit that they saw that democracy was not compatible with a concentration of wealth. Many of them chose wealth.

And so they created a constitution that wrapped popular rule in layers and layers of control that made it hard for the “leveling spirit,” as they called it, to make big changes. It’s kind of like giving the car keys to a teen who just got their license, but then insisting that they sit in the passenger seat, saying, “Hey champ, you can be the navigator!”

Many of the structural limits they designed are still with us— like the presidential veto, the Senate, the Electoral College, and life appointments for the Supreme Court.

Other people (including a few who were at the convention) have spent the last 235 years trying to pry open those layers to create more democracy. Sometimes they have been successful, and so we have the Bill of Rights and 27 constitutional amendments. The anti-democracy team have spent that time coming up with new ways to limit popular rule (check out S4 E8: The Second Redemption for the story of the current right-wing anti-democratic movement). The current battles over voter suppression, gerrymandering, and straight-up neo-proto-facism are part this long fight.

There have been a few shining glimpses of democracy.

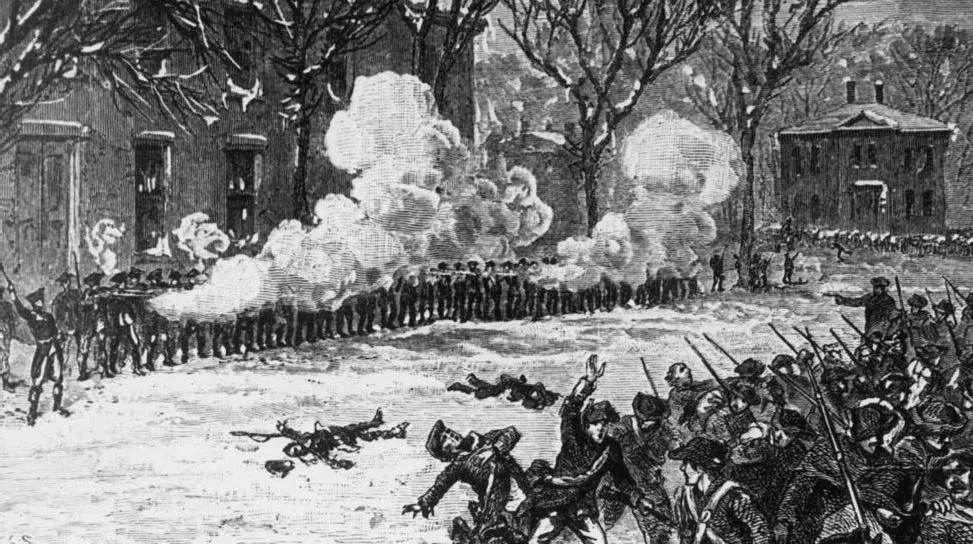

Every now and then things have lined up just right and, at least for a brief time, democracy breaks through. One of the brightest glimpses of what democracy could look like happened right after the Civil War, during what historians call “Reconstruction.” S4 E4: The Second Revolution tells this story.

Right after the war, Lincoln’s Republicans held both houses of congress and were ready to stir things up. Many of them had been abolitionists since before it was cool and wanted to not just end slavery, but reform the South to be racially equitable.

They made some big changes:

They passed three constitutional amendments, outlawing slavery, giving all citizens equal protection under the law, and making it illegal to prohibit people from voting based on race. Some historians have argued that these amendments were not just minor adjustments, but changed the nature of the whole constitution, in the direction of inclusion and representation.

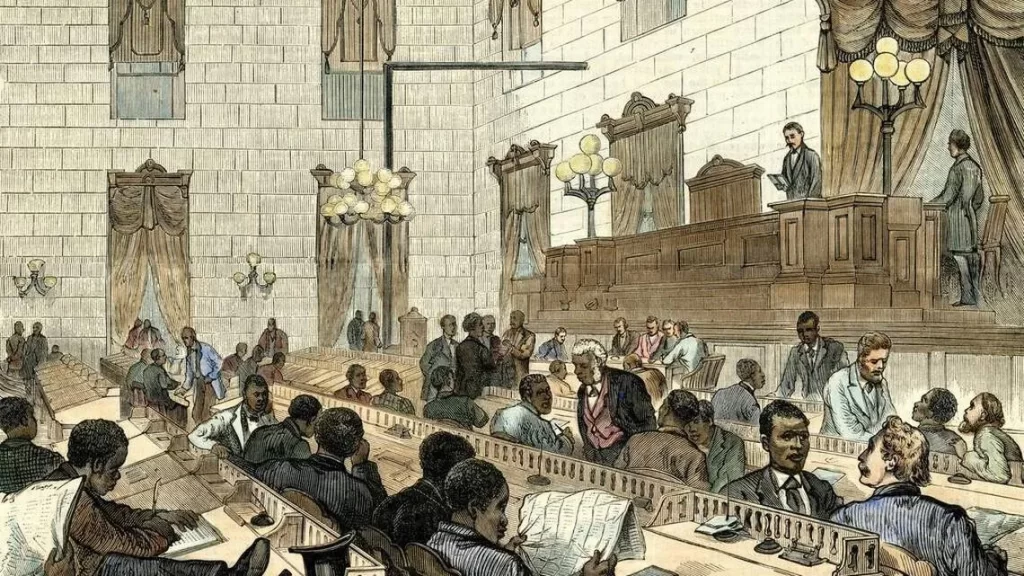

The former Confederate states also had to write new state constitutions. The amazing thing is that the state constitutional congresses were required to have proportional representation of the states’ whole population, including of the formerly enslaved people, and confederate leaders were banned from attending. The actual people created their own state governments. And they created governments far more democratic and inclusive than what came before.

The results were amazing. Something like 2,000 Black men were elected to state offices across the region. South Carolina, for example, had a majority Black state congress. The newly democratic states immediately went about making life better for people, with new schools, integration of public life, and so on. For a time the flagship campus of the University of South Carolina was 90% Black. It looks like things were better for everyone except former slave owners, but I have exactly zero tears for them.

It wasn’t smooth sailing, though. Everything the new legislators accomplished was done in the face of paramilitary, vigilante, and individual violence, especially against Black men. People who wanted to keep the old racial and political order murdered some 50,000 people over the course of 10 years. Even the presence of the army wasn’t enough to stop the violence. But still, people bravely went on building a new and inclusive world.

There was a fatal flaw, though— the federal reforms focused on political equality but didn’t change the distribution of wealth. There were a few people in Congress who argued for distributing plantation land and wealth to the people who had been enslaved there, but the mainstream of the party couldn’t see their way to that kind of change. The result was that while Black people in the South could vote and take office, without land or money, their options for making a living were limited. Meanwhile the former slave owners kept their immense wealth along with all the kinds of power that brought.

In the 1870s, there was an economic downturn during which rich people in the North and South rediscovered their common interests, and northern merchants, bankers, and factory owners lost interest in reconstruction. Federal support for the reconstructed states faltered and soon white people had seized control of the Southern state legislatures and re-rewrote the constitutions to once again exclude the majority of people. Jim Crow laws forced the Black population back into a marginal, oppressed position. Meanwhile all of the social and educational programs created during reconstruction were abandoned. Overall, things got a lot worse for everyone, except the former slave owners.

W.E.B. DuBois (historian and activist) said of this moment: “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery. … Democracy died save in the hearts of black folk.”

Ultimately, it’s a tragic story, no doubt about it. But I find it clarifying in a few ways. First: it’s possible to redesign a government and it takes very little time for a truly democratic government to start making things better. Second, if you don’t address all of the dimensions and forms of exclusion and oppression together, you’ll leave cracks that can be used to undermine any partial gains.

Today, we’re trying to create democracy, not just defend it.

So what do we do? In the last episode of the series (S4 E12: More Democracy), John and Chenjerai turn to the present and future. The last episode came out during the 2020 uprisings that followed the police murder of George Floyd (and far too many other Black men and women), at a time when we saw a huge outpouring of democratic expression. Against that backdrop they talk about practical steps to build a democracy in the US. The full discussion of ideas is well worth listening to, but a few highlights:

Make elections better by expanding voter rights (with something like the For the People Act of 2021), stopping gerrymandering (by having non-partisan designed election districts), and limiting and/or balancing corporate election spending. All straightforward fixes, despite the difficulty in getting them passed.

Fix the constitution. John and Chenjerai talk with legal scholar Sandy Levinson about ways that the constitution could be rewritten to create a more democratic government. Levinson has ideas: 1) to replace the Senate with something more representative, 2) reign in the presidency by making the presidential veto less powerful and impeachment easier, and 3) switch the supreme court to 18 year terms, staggered so someone cycles out every two years. Those all sound promising, but the point isn’t that Levinson has the answers. The point is just to show that the dysfunctional structures aren’t permanent— it is totally within our power to have a constitutional convention and redesign the system. Not easy, but possible.

Organize as communities and in unions to push for changes that better distribute economic and political power.

One thing I appreciate about this to-do list is that as hard as it is, it isn’t a rear-guard action. It’s not about holding back a “red wave” or maintaining old norms. It’s about working on creating something new— an actually existing democracy in the US.

So the bad news is that our current crisis isn’t a weird anomaly in US history and the solution isn’t as simple as defeating specific candidates and electing others (though that’s important). Instead, an anti-democratic move in the service of economic and racial inequality has always been part of the picture. The US has never been a shining example of democracy (sorry, pocket-constitution guy) and there isn’t an earlier time of “normal” to get back to.

The good news, though, is there have always been people trying to create a democracy and break down inequalities. There have been successes along the way and a few glimpses of how things could be. There are also concrete changes that could fundamentally change how the game works. I know I’m tired of the dread and I’m ready to say, “hey, put away the damn dynamite, let’s do something else.”

I’d love to hear from you. What’s your vision for a living world? What projects and ideas are you excited about? What topics do you want to see here? What am I missing? Let me know in the comments.