There’s a scene in the Netflix show Sandman, where Morpheus, the beautifully sour-faced king of dreams, seems defeated. He’s locked in a magical shape-shifting poetry battle and has to transform into something more powerful than “anti-life,” which is the ultimate universe destroying downer. For a moment he seems to have lost. Darkness closes in. Then, at the last moment, he makes a comeback by turning into a post-punk motivational speaker with the answer: hope beats anti-life. He wins the fight, the sun comes out, and I assume everyone has cupcakes to celebrate (we don’t see them in the show, but how else would a magic contest end?).

It turns out I’m a sucker for surreal motivational speeches because I keep thinking about this scene.

Personally, at the moment, I’m feeling a bit like Morpheus facing anti-life. It’s not just because I’ve been listening to the original goth band, Bauhaus, on repeat1— There’s family and work stuff that’s not the best. It’s the tenth anniversary of my dad’s death. And I don’t even need to look at the news to know that something really worrying just happened. Not to mention that decades of social and political progress are being actively dismantled. And I’m on edge about the upcoming elections. Things look bleak. I feel that creeping, cold dark.

So what about hope? The show isn’t specific about how hope defeats anti-life, or about what those of us who aren’t an immortal manifestation of the collective unconscious can do. So I’ve been digging around for more.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

Ernst Bloch, the mid-century German Marxist philosopher, has written a lot about hope. A lot. His book, The Principle of Hope has three volumes, fourteen hundred pages, and very few paragraph breaks, but it is also a detailed account of dreams, fears, and the role of hope in creating a better future. He wrote it during World War II, at a Harvard library, while he was a refugee from Nazi Germany and unable to find work, so maintaining hope in the face of anti-life was an intensly present concern for him. It’s tough going, but the ideas are worth it. I’m also drawing on Kathi Weeks’ summary of Bloch in a chapter in her book, The Problem with Work.

Hope is partly a personal thing, but it’s also a powerful part of social movements. It’s that pull toward a better world that gets people moving and charts a direction forward.

As I’ve been picking through the philosophy of hope, I’ve found a few ideas that I find helpful in being more hopeful, both for myself and for the world.

Here is what I’ve learned about hope:

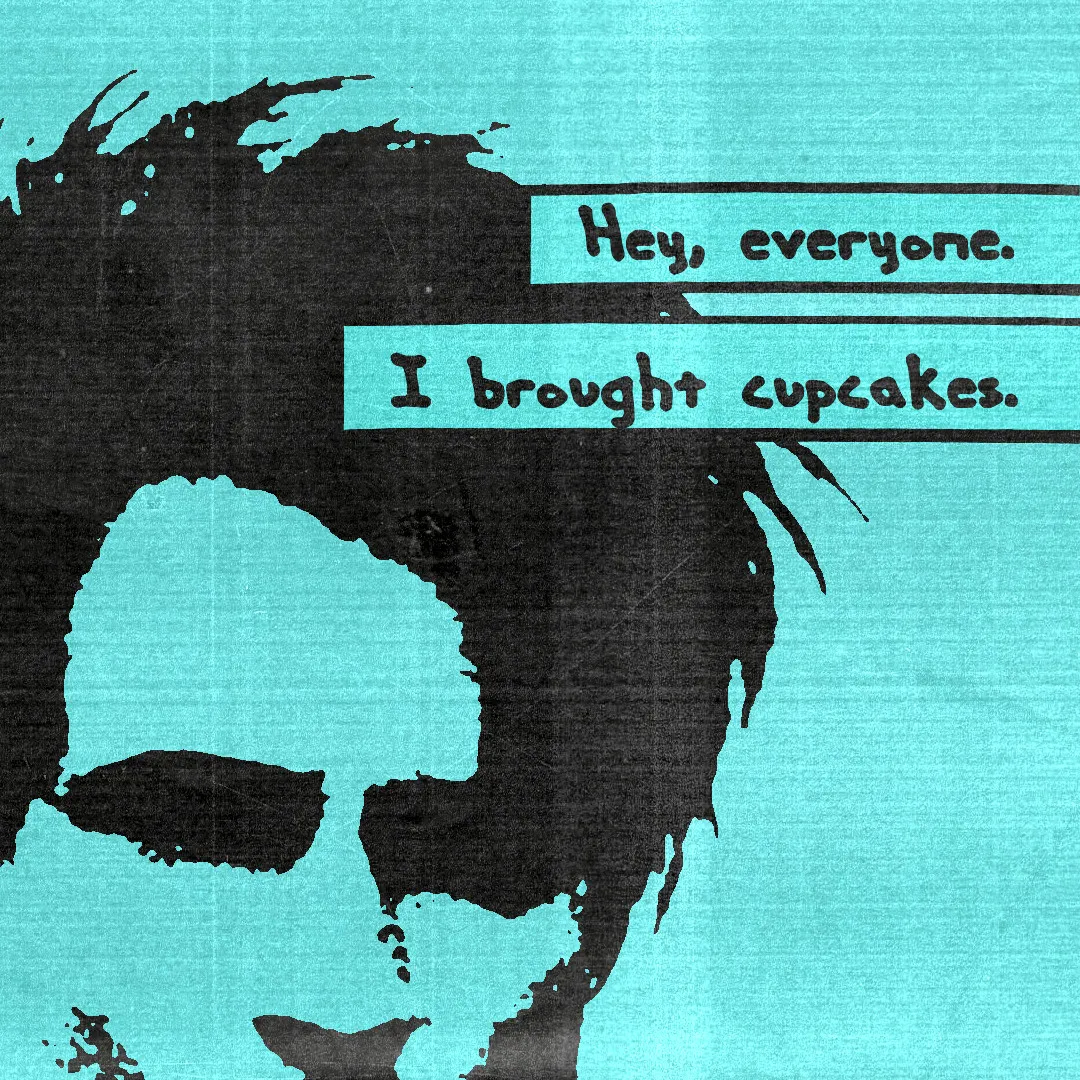

Hope is like memory, but for the future.

In Bloch’s account, remembering and hoping are specific activities. Remembering is thinking about the past. Hoping is thinking about the future. They are things you do. And things that you can practice. Maybe this is obvious, but I find it really helpful.

Let’s take a moment to try remembering. Close your eyes and remember a moment of peace or maybe a moment of connection with someone. Try bringing the whole experience of that time and place to mind. The sounds, the feeling of the air, the feeling of your body, the whole sensory experience.

I’m remembering sitting on a beach in South Carolina on a foggy December afternoon. I’ve been sitting with my eyes closed and when I open them, my 18 month old daughter is right there grinning at me.

There are lots ways to think about the past. Some are straightforwardly practical, like recalling specific facts. Some are unhelpful or unhealthy, like ruminating, dwelling, or pining. But then there’s this more expansive and gentle remembering that can bring those experiences, those moments or people back into the present. When I pause to remember this way, I find it really grounding and comforting. Even though this is a basic capability, I find it amazing that at any time I can bring back any other moment.

Similarly, there are many ways to think about the future. There’s the practical— predicting and preparing. Which are useful enough.

And of course, there’s worry and anxiety, which are favorites of the part of my brain that doesn’t want me to sleep. These are certainly unpleasant, but for Bloch, there is more at stake. He writes about how fear and anxiety make people smaller and less connected. He says fear “cancels out the person.” Individually, those ways of thinking about the future reduce a person’s horizon of possibility, leading them to desperately grasp at the present. Socially, it leads groups of people to jettison higher ideals and to follow anyone who promises to make things less scary. Thomas Hobbes, a king of anti-democratic thinkers, thought fear was great because it made populations easier to control. Bloch was not a fan for exactly the same reason (having fled Germany in 1932, he was clear on the danger).

The counter to anxiety is hope. Like memory, it’s a way to bring another time into the present. You could see hope as a way to pull positive possibilities into the present. It’s like getting enough balloons that you’re not sure your feet are going to stay on the ground.

Let’s try it. Close your eyes and cast yourself into the future. Imagine yourself in a specific place. Picture the sounds, weather, and so on. In this future things are going well. You’re comfortable, energized, and relaxed. There’s a key problem that isn’t an issue any more. Imagine that there’s something you currently wish that is simply true. You don’t have to fill in all the plot details, just try to feel what it would be like to really be there.

Just as remembering can be grounding and comforting, hoping can be uplifting and energizing. Bloch says that: ‘‘the emotion of hope goes out of itself, makes people

broad instead of confining them.’’ This feeling of expansion and extension is a key ingredient for building vibrant lives and social movements.

Everyone remembers and hopes to some degree as a matter of course, but Bloch urges us to consciously practice these helpful ways of relating to the past and the future. The more you do them, the easier they are. That said, Bloch is a good start, but for me, therapy is totally necessary for learning these ways of thinking and I’m discovering that coaching helps, too.

I’ve been mostly talking about individual hope and memory, but you could see a precise equivalent with collective memory (history) and collective hope (social movements). There are different ways to think about our collective past and future, some of which are grounding and inspiring, some are anxious and destructive. Bloch thinks that social change can only happen if we can practice those helpful ways of relating to the past and future.

The future will be a surprise.

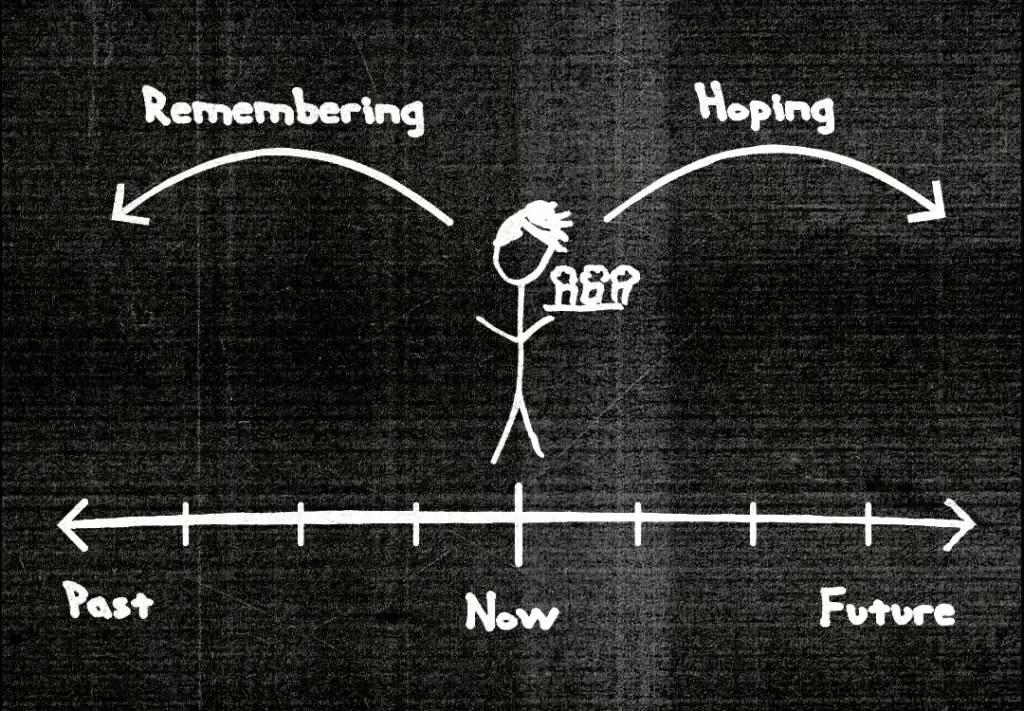

For Bloch, hoping is balanced between prediction on one hand and wishing on the other. If prediction is following the trend lines to a likely future and wishing is jumping to some ideal, hoping is the knack of doing both at the same time.

Let’s try it. Go back to that imagined scene. Think about how things are different from the present. Now imagine the change is a little bigger— let yourself mix in a little more wish into the daydream. Does it feel different? Add a little more. And a little more. There’s a tipping point where it feels like the anchor starts to slip and the daydream drifts away into fantasy. The trick with hope is to pull back before the slip happens.

Bloch has two technical terms that might be helpful.

He calls the anchor to current reality the “real-possible.” Hope doesn’t work if there’s no imaginable way to get from where you are to where you want to be.

Bloch calls the pull toward the fantastic “the novum,” or just “the new.” This is the aspect of the future that is totally different from the present. It is the thing that you can’t predict. It’s a word for the element of radical difference that makes the future unexpected or even unimaginable. Hope always has a soft focus because it’s not about certainties or straightforward goals— it involves an anticipation of something new and surprising. Hoping is like knowing you’re going to get a present, but not knowing just what it will be.

Daydreaming is part of understanding the world.

This business with remembering and hoping might sound pleasant, but it might also sound like a distraction from reality. I know there’s a little voice that tells me to stay focused on whatever is at hand and not get distracted by the past or the future, especially not by daydreams (that work-obsessed wind-up toy on my shoulder is still at it). I start to think that maybe I ought to work on a spreadsheet or at least face the up to the limited range of immediately realistic action items.

Ernst Bloch says otherwise. For Bloch, staying focused on the present is only “realistic” if you have a very limited idea of what counts as real. Instead, he argued for a more inclusive idea of reality in which the past and the future are real, right here and now. This might seem abstract, but I think it’s the key to the anti-life defeating power of hope.

Here’s how it works:

Everything and everyone in the world is always changing. Instead of thinking about static things, Bloch asks us to imagine interconnected processes. Right now is just a moment in the processes of things changing from how they were to how they will be.

That means that they way people and things are right now only makes sense if you know where they came from. You need memory and history to understand the present. So far this feels like familiar territory covered by every history-related grant application ever written.

The process view also means that possible futures already exist. This is where the idea get harder to track. For Bloch, everything is unfinished. It has leading edges and open possibilities. I imagine a ship at the horizon, apparently balanced on the edge of the sea. Or another image— the present contains the seeds of potential futures. Seeing what things could become is an important part of understanding what they are.

Let’s try it. Go back to that imagined future, the one that’s bigger than you started with, but not so fantastical as to be unmoored. Now try to think about that hoped for future overlayed on the present. Like you’re layering photo slides. Where do they line up? What aspects of that future are already part of your present? What seeds can you find already sprouting.

When I think this way, I often find parts of my life and of the world that I hadn’t noticed before. It turns out you can’t really understand things if you’re not daydreaming. And once I see those those seeds, I get some good clues about what to do next. If I help those parts grow, I know I’ll be moving toward a future like the one I’m hoping for.

What I love about Bloch’s version of hope is that it’s an answer to anxiety and disenchantment that is very different from simple optimism or even from general positivity. It’s not about loudly announcing, “It will be fine! It IS fine!” and ignoring problems. It’s not even really about feeling better. Instead it’s a practice that helps us recognize possibilities and gives us permission to reach for them. It helps us know that the future will be new and different and that the seeds of the best version of that future are already here. It’s grounding and uplifting, expanding and connecting. And maybe most importantly, Bloch’s version of hope invites us to get to work tending those possibilities.

In the Sandman show, Morpheus generally solves the problems he faces by learning better ways of being in the world. (Wait, does it turn out that Sandman is Ted Lasso, but for goth kids?) Sometimes he expands beyond the problem, like earlier in the poetry battle when he becomes a life-embracing world as way to overcome a deadly bacteria. Othertimes he learns to be more grounded, humble, and connected to those around him, like later in the season when the world is saved because he learns to stop being a terrible boss and collaborates instead. What I love about the hope moment is that it’s both rooted and connected, and all-embracing and sublime.

Working through these ideas, I realize that this whole newsletter project is a practice in hope. I’m scanning for those glimpses of a possible future, searching for the seeds in the present, and scouring the past for clues about what might be possible. In comparison to anti-life, a hopeful vision and a living world might just be the same thing.

We’ve been in bleak times for a while. I think many of us have had plenty of practice with anxiety, fear, and despair. I know I have. So, I’m going to keep trying to get the hang of the shafe-shifting magic trick of hope. I’m sure Coach Morpheus will break out the cupcakes when I get it.

For more on Bloch’s philosophy of hope:

Menozzi, Filippo. “Militant Optimism: A State of Mind That Can Help Us Find Hope in Dark Times.” The Conversation.

Thompson, Peter. “The Frankfurt School, Part 6: Ernst Bloch and the Principle of Hope.” The Guardian, April 29, 2013.

I’d love to hear from you. What’s your vision for a living world? What projects and ideas are you excited about? What topics do you want to see here? What am I missing? Let me know in the comments.

A gloomy band to be sure, but even so, the last song on their last album is called “Hope.” “Hope.”