Last week I wrote about Christopher Alexander, an architect who wanted to create places where communities and individuals could flourish. This week I’m thinking about how living places are created and how they work. Alexander has some ideas and tools that are useful.

A better world is possible. Subscribe to learn how to build it!

Bringing a place to life

If you’re going to plant a garden, build a house, arrange a room, or improve a neighborhood, how do you know what will increase the life of a place?

Alexander and his colleagues at the Center for Environmental Structure had many specific suggestions:

Neighborhoods should have an identifiable boundary

Most building should be four-stories or less

Every community should have a promenade that links main activity nodes

Window seats are inviting and comfortable

Rooms should be roughly square

Kids love stages and caves

People love to sit on a low wall.

These suggestions are really more like rules of thumb that describe the common features of good places. These aspects transcend the specifics of particular times and places. He called these common features patterns.

A pattern is the essence of a solution to a ubiquitous problem. It is a way to resolve the forces that people feel in a certain situation. It’s not a rule to follow mechanically but rather a seed for growing a local solution. Every time a pattern is used in a specific situation the result will be different, though the effect will be the same.

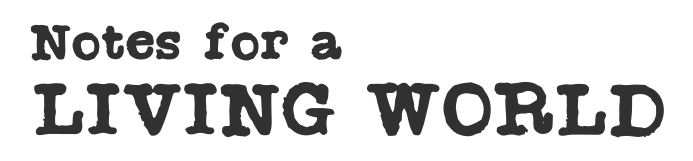

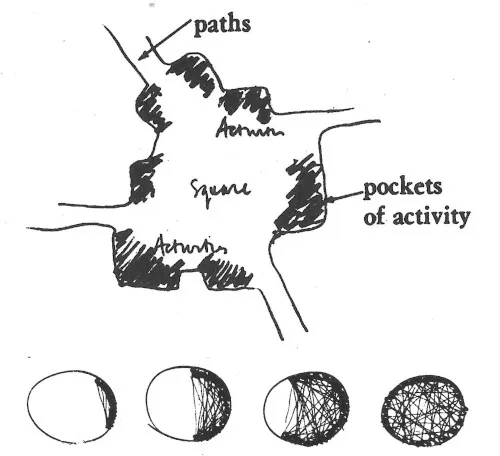

Here are two example patterns, activity pockets and the intimacy gradient:

Alexander worked with some colleagues to write A Pattern Language, which outlines 253 of these of patterns. They range from patterns for regional economies and transportation, down to the position of chairs in a room. Along the way, they touch on education, public spaces, gardens, roof design, and room arrangements. It covers every scale of the built world, though it’s not a master plan or a centrally controlled vision.

You can pick up this book and start making places better.

Alexander’s practicality is important because he believed that everyone has the ability to create living places. They are not created by architects, planners, or developers. They are not designed at a drafting table. Instead they are tended and grown over time. Living places are more like plants, which unfold from a seed, unlike machines that are assembled piece by piece.

To create a living place people make small changes, one at time, to enhance life-giving aspects and diminish the deadening aspects. The process can be done by one person arranging their own space, by a group of people sharing a house or collection of houses, or by larger communities at the scale of a neighborhood, city, or region.

A corollary of this process is that any place can be as beautiful, whole, and lively as any place in history— if you make a garden in this manner, it has the potential to be as lovely as the most wonderful garden in the world, no matter where it is or how limited your resources are.

But it’s not easy. It turned out that just following the patterns isn’t enough. Alexander posited that we need to develop a feeling for a deep quality, which is a more complicated and subtle aspect of his theory.

See the life in everything

For Christopher Alexander, the key to creating good places is being able to sense the amount of life in a place and then imagine ways to increase it.

Life in this context is a very specific phenomenon. For Alexander, each thing has a degree of life. Not just biological organisms, but everything. Tables, cups, lamp posts, streets, not to mention rocks, rivers, and actual organisms. This isn’t a spiritual statement, but a description of a concrete quality that anyone can directly sense. Something is alive if it feels whole and true.

The process is simple, weird, and maybe profound. Here are Alexander’s instructions: Choose two objects; look at them and pick which brings up a feeling of wholeness. This is tricky. It’s not a matter of which one you like more. It’s not a matter of style or taste. It’s deeper. Ask yourself: which is more like your own self? In Alexander’s words,

…which comes closer to being a true picture of you in all your weakness and humanity; of the love in you, and the hate; of your youth and your age; of the good in you, and the bad; of your past, your present, and your future; of your dreams of what you hope to be, as well as what you are?

It’s a lot, I know. But let’s try it. Here’s a warm up:

In an exercise where Alexander prompted people to ask whether the salt shaker or ketchup bottle was more like themselves, he found most people don’t want to answer at all. When he insisted, the overwhelming majority of people picked the salt shaker. What did you pick? In general, asking this question produced remarkable agreement in people across the board. Alexander claimed, the perception of “selfness” isn’t a matter of preference, but an of an objective quality that is paradoxically independent of the individual.

Alexander is going against the grain here. Folks these days are rightly wary of any claim to universality. And this is enough for some people to discount his whole project. I think what saves it, though, is that while recognizing life is universal, creating living things or places is always rooted in a particular culture, time, and location.

Let’s try another. If you have some US coins handy, compare a nickel and a dime. Which is a better picture of your true self? It seems like the answer should be “neither,” but oddly, when I do this, it’s definitely the dime.

And one more, that gets us back to the built world:

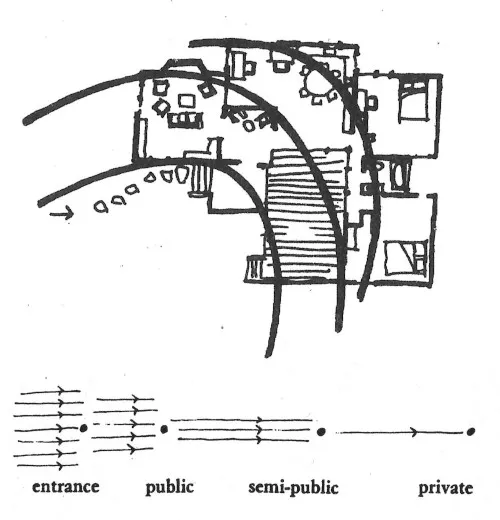

Did you choose the image on the left? You can do this with buildings, rooms, or objects. If you practice, you’ll get a better and better sense of what the phenomena of life means for Alexander.

You might also realize how rare this feeling is in places made in the past 80 or so years. The concrete plaza around an office tower? A highway overpass? The Georgian-style columns of a fancy tract home? “No,” to all of them. On the other hand, if you go back to the pictures in last week’s newsletter and ask the true-picture-of-yourself question, do you find a clearer sense of the difference in these places?

Designing for life

When the feeling for life is combined with pattern languages, spaces and places almost design themselves. Alexander describes the design process as a matter of going to the location (or imagining it), then calling on the feeling of wholeness to picture the most intense version of whichever pattern applies. If it’s a courtyard, you call to mind the most lively courtyard possible. If it’s an entryway, you hold the feeling of the most welcoming entrance in the world. The place you’re working on will resolve itself in your mind’s eye as if it already existed. Repeating the process with other patterns can then help clarify more and more aspects of the design.

This feeling for life can also give groups and communities a way to come together around placemaking. Because everyone can learn to recognize this quality, it can be a basis for collective decision-making. It gives a common goal that transcends the individual interests people might bring. More that that, the process itself creates and deepens a community. If a group can really dive in and ask if such-and-such a design reflects themselves in all of their complex wholeness, if they can stand in a location and together imagine a fully living place, they can build new kinds of shared understanding and a deeper shared vision of what they could be.

Ultimately, it’s this shared process and shared understanding instantiated in the built world that creates places where people can really come alive.

More summaries

This post is just one slice through Alexander’s ideas. Other summaries highlight different aspects. Here are my favorites:

A great overview of his ideas: Project for Public Spaces, “Christopher Alexander,” 12/31/2008.

Here is a summary of The Nature of Order, a four volume master work.

A blog post about Alexander’s patterns related to education: Henrik Olof Karlsson, “Christopher Alexander’s Architecture for Learning,” Escaping Flatland, March 22, 2022.

Books

If you want to dive deeper, reading Christopher Alexander’s books is the way to go. There’s something about the accretion of his many photographs, examples, and restatements that makes it all come alive. Here are some key books:

Alexander’s first major essay, later published as a book, contains the kernel of the later work: Christopher Alexander, A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, 2019.

A guide to the original pattern language, adds up to a compelling vision of a humane world: Christopher Alexander, et al, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

A companion to A Pattern Language, explains the underlying ideas and process. Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Often referred to as Alexander’s “masterwork” these four volumes explore the phenomena of life in buildings, communities, and objects, both a practical guide to creating living places and things and a deep consideration of the role of order and human feeling in the universe: Christopher Alexander. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Center for Environmental Structure Series ; v. 9-12. Berkeley, Calif.: Center for Environmental Structure, 2002.

Are there places you’d like to bring alive? Are there ways that you’ve changed a place that has made it more comfortable and humane? Let me know in the comments!